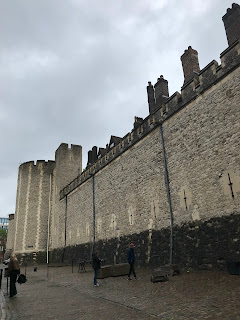

Drier weather for the Tower of London, praise the lord, but still pretty dismal. Not postcard weather. First impressions as you enter is how vast it is; rather like the Tardis, it appears larger on the inside than on the out. Occupying 18 acres, it's like walking into a small town, tourists providing the bustle in lieu of those who would have worked there five or six hundred years ago.

The Bell Tower

The tower was built in the late C12th, possibly by Richard the Lionheart, to strengthen the defensive wall of the Inner Bailey. Over the years it has held such prisoners as Saints Thomas More, and John Fisher—the only bishop who refused to sign Henry’s Act of Supremacy. In recompense, the Pope promised to make him a cardinal. A furious Henry reacted that Fisher would have no head to wear a cardinal’s hat or any other kind of hat; true to his word, Fisher was decapitated in 1535.

The protestant princess Elizabeth, seen as a threat to her half-sister, Mary I was also imprisoned in the Bell Tower. She would have been acutely aware that her mother, Anne Boleyn had been executed just yards away, but despite heavy and prolonged questioning, nothing could be found against the twenty-one year old, and she was eventually released. The battlements between Bell Tower and Beauchamps Tower is still known as ‘Elizabeth’s Walk’ the limits of her freedom during captivity.

The Bell Tower to the right, augmenting the inner curtain wall

Edward's bedroom, the table sometimes serving as an altar allowing him to attend Mass in bed

It was here or in an adjoining chamber we enjoyed watching an actress dressed in medieval costume talking to a group of twenty primary school children. She was talking about medieval weapons, asking them what kinds of weapons might have been used in those times.

A spear!

Sword.

Bow and arrow.

The answers came thick and fast—until they didn’t.

She regarded them earnestly. 'Anything else?'

A long pause. A hand. ‘Melons.’

Such are the joys of teaching.

The Martin Tower was built by Henry III and used as a prison, housing such guests as the ‘Wizard Earl’—Henry Percy 9th Earl of Northumberland, and eleven German spies before their execution during World War I. Between 1669 and 1841 the tower stored the crown jewels and became known as the Jewel Tower.

In 1670, the adventurer Colonel Blood bamboozled the seventy-seven-year-old deputy keeper of jewels to gain entry. Once in, they bashed the old man on the head and stabbed him for good measure. The crown and orb were stolen, the sceptre stuffed down one of the conspirator’s breeches, but they failed in their escape. The aftermath is more interesting. Blood refused to answer any questions until he’d seen the King. Charles II was so taken with him that Colonel Blood was not only released but granted an estate in Ireland worth £500 a year. Bear in mind the poor old Deputy keeper who somehow survived the attack was awarded only £300 compensation which was never actually paid, and three years later he died.

Why would the king pay a pension to one who’d tried to steal the crown jewels? There are several theories—the king admired a fellow adventurer; alternatively the king, always short of money, was in fact the mastermind behind the theft. Whatever the case, Blood died in 1680. He did though leave descendants. In 1879 Field Marshall Sir Bindon Blood commanded the Malakand Field Force safeguarding the North-West Frontier, today's Pakistan. Bindon Blood handpicked his officers for boldness and courage, one of whom was Winston Churchill.

The Salt Tower

This tower has held many prisoners over the years, including the King of Scotland, John Balliol imprisoned by Edward I, and Hew Draper, a Bristol innkeeper, who was accused of practising sorcery against Bess of Hardwicke and her husband. Draper claimed he’d burnt all his magical books. Even so, he carved this large, complicated astronomical clock upon the wall of his cell. Passed the time.

“Hew Draper of Brystow made this sphere the 30 daye of Maye anno 1561”

Catholic symbols are also scratched on the walls, largely done by Jesuit priests imprisoned here as the threats against Elizabeth I intensified.

The most famous of the Jesuit prisoners was John Gerard who was suspended by chains and tortured. And yet, he escaped! A rope was suspended from the Salt Tower across the moat, and despite wrenched arms and mangled hands, he succeeded in crossing the moat to be spirited away by the Catholic underground.

There are 21 towers in all, but you can have too much of a good thing.