My wife, mathematician and art-lover, has opened so many doors in my life, most recently artists, and exhibitions I would never have otherwise gone to. The most recent one was the Pissarro exhibition at the Ashmolean, where I was reminded again how great art, prejudice and mean-minded passion can mix a cocktail of poison.

Camille Pissarro 1830 – 1903 was born in the Virgin Islands but with his family, re-settled in Paris. From the start, he revealed an independent mind, disappointing his conservative Jewish mother and father by marrying their non-Jewish maid. It was a wise choice, for her work ethic subsidised his early, precarious artistic career, as well as gifting him eight children.

The former maid, Julie Vellay and Camille Pissarro

In fairness, Pissarro was equally generous, especially to younger artists such as Degas, Cezanne, Gaugin and Renoir.

And then everything changed. In 1894 the Dreyfus Affair erupted and split France as bitterly as Brexit or MAGA today. Alfred Dreyfus came from an Alsace Jewish family and became the highest-ranking Jewish artillery officer in the French army. In 1894 he was accused of treason, passing military secrets on to the Germans. Antisemitism exploded, confirming the prejudice that the rootless Jew owed loyalty to no particular country. When it was later discovered the real traitor was Major Ferdinand Esterhazy, an impoverished French nobleman, the fact was covered up to save embarrassment, and Dreyfus was imprisoned on Devil’s Island off the coast of South America.

The case split France as well as a previously close-knit artistic community. Despite his Jewish background, Pissarro as a radical anarchist, hesitated before leaping to the defence of a wealthy military officer of rank, but when he did so, his commitment was complete along with Monet and the writer Emile Zola. For Pissarro, injustice was injustice.

Some of his oldest friends, Degas, Renoir and Cezanne, took the opposite view, the first two revealing an almost rabid antisemitism. It must have hurt Pissarro profoundly when his old friend Degas crossed the street to avoid talking to him. Renoir went further, denouncing Pissarro’s family as part of "that Jewish race of tenacious cosmopolitans and draft-dodgers who come to France only to make money.” He linked this to Pissarro’s sons who had failed to do military service precisely because of this 'lack of loyalty'. In 1882 Renoir protested against showing his work with Pissarro, arguing that ‘to exhibit with the Jew Pissarro means revolution.’

Camille Pissaro in old age. Self Portrait

Pissarro continued to admire Degas’ work. Degas on the other hand suggested that Pissarro’s art was ignoble. When reminded that he had once praised it, his response was ‘Yes, but that was before the Dreyfus affair.’

The elderly Pissarro and family

Degas was the loser in this, degenerating into an almost mad caricature of the antisemite, but this post is about Camille Pissarro. Below are the paintings that caught my eye, some giving you the illusion you could almost walk into them, else seeing them from a window and wishing you could.

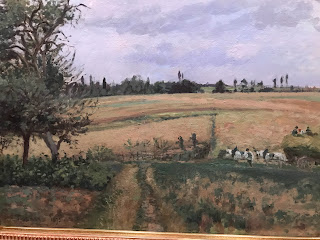

Landscape near Pointoise. The eye initially takes you to the rickety fence before catching a glimpse of the hay cart moving in from the edge of the picture. This is one of Edgar Degas' favourite pictures and he continued to own it until his death. Which is ironic

The Pea Stakers Here, realistic toil is replaced by colour and grace. The women are planting poles to train pea plants, but it looks as though they are dancing.

Village seen through trees A nice medley of green and brown with small patches of brilliant reds and blue. A sense of real homes and a community at work oblivious to anything outside of the frame.

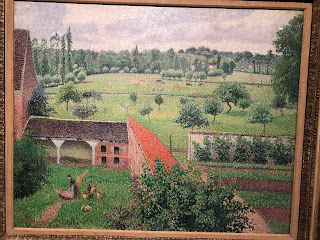

View from My window. Pissarro described it as 'primitive modern' and was distressed when his dealer said it was unsaleable. It reveals the view from the first floor of his house in Eragny

Man sawing wood - Pointoise

Lucien Pissarro, the eldest and perhaps favourite son. An artist like his father who continued the impressionist tradition. He moved to London permanently in 1890 and died in 1944 having influenced a whole generation of British artists. You feel as though he might turn and smile at you on the moment.

One of Lucien's impressionist works

"Rodo" Pissarro's fourth son aged four or five. Pissarro catches the nervous smile.

One of the nicest experiences at the exhibition was seeing how a group of thirty junior school pupils reacted to him. I inwardly groaned when they entered en masse , but within ten minutes they had split into groups of three and were studying each painting, engrossed and discussing what they saw in them. After a time they sat and sketched their favourite painting. The old man looking down at them would have been as pleased as punch. Degas, perhaps less so.