Some weeks ago we went to visit the Gaia exhibition then installed in Wells Cathedral. Created by the artist Luke Jerram, it measures seven metres in diameter and is created from 120dpi detailed Nasa imagery of the Earth's surface. It allows us to see the world floating in three dimensions. Believe me, I take a dim view of installations in Cathedrals ever since one hapless bishop installed a helter-skelter. But this installation is truly inspired. If you ever want to see it, the tour dates are here. If you're unable to, what we have here is your best shot, and at least it will be hard to beat this setting.

The City of Wells is named after a series of streams which flow into the moat of the Bishop’s Palace

The palace was built by Bishop Ralph of Shrewsbury, a man despised by the citizens of Wells for his heavy taxation, hence the crenelated walls, drawbridge and moat. Ralph was no fool.

But now onto the star of the show, the cathedral itself.

Here, around 705 AD King Ina of Wessex built the first Saxon church, dedicated to St. Andrew. The font from this first church is still here.

The original Saxon font

In 766 AD, Cynewulf king of Wessex (I wish I’d been called Cynewulf. Cynewulf Keyton) endowed the church with eleven hides of land, and in 909 AD, Athelm, first Bishop of Wells, made the church a cathedral. Even before the Norman Conquest of 1066, there had been thirteen Bishops of Wells.

There are few traces of that original church now. By 1150, it was deemed too small and in 1175, work started on its replacement—one of the finest examples of the Early English Gothic style—and consecrated in 1239.

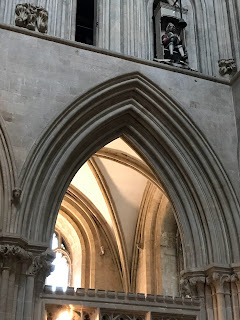

It continued to develop after 1300 AD culminating in the great central tower, which a few years after showed signs of subsidence. The medieval solution was to support it on three sides with ‘Scissor Arches’ below

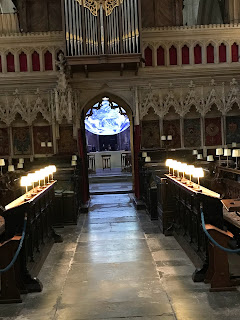

The English Civil War did it no favours. Fighting destroyed some of its stonework, furniture, and windows. It also cost Walter Raleigh his life–– No, not that one. Dean Walter Raleigh was a nephew of the great explorer and inherited much of the great man’s poor luck and timing. He was placed under house arrest by the Roundheads. His gaoler, a cobbler and city constable, David Barrett, caught him writing a letter to his wife. When he refused to surrender it, Barret ran him through with a sword. Raleigh died six weeks later and was buried in an unmarked grave in the choir before the Dean’s stall.

The cathedral suffered a final crisis during the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685. Soldiers damaged the west front, tore lead from the roof to make bullets, broke the windows, organ, and smashed furnishings. Their horses were stabled in the nave. In my view they deserved all they got from 'Hanging Judge Jeffreys,' though that may be considered an extreme view.

The Lady Chapel has/had some glorious windows. The one damaged by said rebels has been patched together in no particular order. It's now a colourful jumble which bears more witness to the vagaries of history than Christ and his saints.

Various views of the Lady Chapel and its windows. See if you can spot the 'kaleidoscope window'

A melancholy memorial to the late Bishop Richard Kidder and his wife killed in the great storm of 1703 when two chimney stacks on the palace fell on them while they were fast asleep in bed. Bit of a nightmare.

Another glorious composition of arches, but it is John Blandiver (top right) you need to be looking at, an essential component of the second oldest clock in the world. See below.

Iconic steps leading up to the Chapter House where the Cathedral's governing body sat beneath brass plates. These record the parcels of land that paid for this and that in the Cathedral. It was completed in 1306, so those steps have had some use.

Like everything else in the Cathedral, it is a masterpiece of harmony and composition.

John Still, Master of St John's College Cambridge, 1574

No comments:

Post a Comment