One of the finest biographies I've read

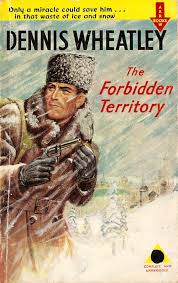

Dennis Wheatley was at one time a colossus of British popular fiction, best known for his Gregory Sallust series, the Roger Brook books, and of course the series featuring the Duke de Richelieu and the Satanic series brought to life in, ‘The Devil Rides Out.’

And yet, almost up to last breath, he bemoaned the fact that he had never made it in America, a fact waspishly celebrated by a fellow writer, Sam Youd: “If, in America, you cannot reach Wheatley, thank once again the deity who created your native land, for we, in England, cannot get away from him.”

In this respect, Wheatley shares the fate of W.E Johns, for Biggles never made it to America either, both perhaps too peculiarly English to survive the transatlantic voyage.

As his biographer Phil Baker explains:

"Wheatley was English, and his whole character embodied the archetype. He believed in an orderly, cohesive and benevolently hierarchical society. He had a grain of eccentricity, a code of good form, allied to a sense of fairness; a sense of voluntary service; a respect for amateurishness; a lasting boyishness…”

The boyishness is, perhaps, the key to it all: romanticism, idealism and sense of adventure, the tendency to simplify and see things in black or white. Small boys are acutely aware of pecking order, and they also tend to collect the weirdest things in their pockets.

The man was the boy, obsessed with penetrating the highest echelons of society (King George VI loved his books), a member of all the most prestigious clubs and involved in operational planning during the war, where he rubbed shoulders with Admirals, Generals, and key members of the establishment. With it came all the trappings of an aspirational schoolboy, one now with vast and capacious pockets.

Wheatley wrote on a mahogany desk, sitting on an Empire armchair, surrounded by Chippendale furniture, a gilt mirror, a Louis XV bookcase, Georgian silver, Dresden china and a plate from Marie Antoinette’s dinner service. There were china figures of Napoleon’s marshals on top of his bookcases. He had a bronze of Napoleon on horseback, ivory figures of French kings, Marie Antoinette and Madame Pompadour and a bronze of Charles I. The list goes on and we haven’t yet touched on his collection of Chinese porcelain include a Ming or two. And yet, pictures of him in his velvet smoking jacket behind the desk upon which he wrote all his novels, you do not sense a soul at ease, rather disappointment, the sad expression of a schoolboy wanting more.

Wheatley was the child of empire, a toddler during the Boer War, a serving officer during World War I who kept a log book of various prostitutes and their proclivities, and an enthusiastic strike-breaker during the 1926 General Strike, who, like many of his class, feared and abhorred the Russian Revolution.

His early years explain much too; the grandson of a ruthless street trader who moved into wine, the Wheatley family climbed the social ladder. Eventually their wine business serviced royalty and great aristocratic houses of Britain and Europe. When family wine business went bust in the Great Depression, Wheatley took to writing and the rest is history.

And, sometimes turning in 16 hour days, the books continued to flow.

Family aspiration brought with it emotional insecurity, accentuated when he was shunted to a minor public school (Dulwich) and HMS Worcester a harsh nautical training school.

Like later comedians who survived school bullies by making them laugh, Wheatley’s strategy was to tell exciting stories and, wherever he went, formed ‘secret societies’ as a small and exclusive praetorian guard.

And finally, the two books he adored most as a child: The Scarlet Pimpernel, and Dumas’s The Three Musketeers. Mix these three elements together and you have the formula for every one of Wheatley's best-selling books, whether it be the three-some of Gregory Sallust, his faithful batman, Rudd and Sir Pellinore Gwayne Cust,—or the Duke de Richeliu, SimonAron, Richard Eaton and the stout-hearted American, Rex van Ryn.

Instead of rescuing aristocrats from the guillotine, these heroes rescue souls from villainous Nazis, Bolsheviks, and the Devil himself —but always, always with the finest of wines, food and cigars.

The bulk of the Sallust and Duc de Richeliu novels were written during World War II, a conflict Wheatley saw as a conflict between light and the forces of darkness. The propaganda was hard-core and well received by the establishment. Maxwell Knight, Britain’s key spymaster, told him upfront that his novels contributed more to the war effort than anything he could do in uniform.

Reading them now is occasionally accompanied by a wry smile, especially when Gregory Sallust lambasts Nazi gauleiters for feeding off the fat of the land while lesser people struggled with ration books. Whilst working in the war office, Wheatley never gave up on the finer things of life and assiduously climbed the social ladder accepting every luncheon invitation that came:

“Lunch at Rules with Eddie Combe was a great invitation” Wheatley remembered. It would start with two or three Pimms before moving on to harder stuff; Combe liked a dash of absinthe or ‘Chanel No. 5’ as he called it. Lunch would consist of smoked salmon or potted shrimps, then Dover sole, Salmon, jugged hare or game, with Welsh rarebit as a savoury to finish. After their wine with lunch, they would end with a port or kummel. Nazi empire or Imperial Britain, different rules applied for those with money. *

In his ‘Gateway to Hell’ Wheatley opens the story with Simon Aron having the Duke de Richelieu and Richard Eaton round to dinner, where he serves them smoked cod roe on toast with a glass of very old Madeira’ Lobster Bisque fortified with sherry, with a 1933 Marco-Brunner Kabinett; partridge with foi gras, with a 1928 Chateau Latour; and finally, a fruit salad of iced oranges laced with crème de menthe. Refreshing their palates with a small cup of cold China tea, they move on to a bottle of 1908 Imperial Tokay and end with Hoyo de Monterrey cigars. An aphrodisiac, before I knew what an aphrodisiac was to a Liverpool boy munching crisp sandwiches, sometimes with ketchup.

*Fish and crustaceans were unrationed there being no shortage. Game was unrationed too. Hotels and clubs could source such luxuries from private estates for those who could afford them. Similarly, wine stored in deep cellars